I have been thinking about grammar in Sacred Scripture. Well, why not? We think about vocabulary when we think about the Bible. We ask what this word means and that word means. We think about manuscripts, because there are thousands of variant readings in the Bible, and different manuscripts which people have made over the centuries have different readings. So why not think about grammar too?

In John’s Gospel (1:38-39), two of the disciples of John the Baptist come to Jesus, and he asks them a question: “What do you seek?” It’s in the interrogative mood, and it really anticipates a reply in the indicative mood: “We are trying to find out more about you”, or some such thing. Instead, they answer with a question: “Rabbi, where are you staying?” Now it is they who speak in the interrogative mood, asking a question. Now they are looking for information, so the natural response to that would again be in the indicative: “I’m staying in Bethany [the one on the east side of the Jordan, not the Bethany by the Mount of Olives], in a house on the main street, three doors along from the butcher’s shop” – or some such thing.

But now Jesus answers, not in the indicative, nor in the interrogative mood, but in the imperative: “Come and see.” He utters a command.

These two disciples are looking for information. Jesus will not give it to them. Instead he calls them to a change in practise, to a way of living: come and see. Our encounter will begin not with information, but with a practice and corresponding experience: come and see. Walk this way.

This touches on one of the themes of God as Nothing. Over and over again, the book stresses the view of Thomas Aquinas, and of many other great teachers of the Christian tradition, that we cannot know what God is. To know God, Thomas says, is to know that we don’t know what he is. Knowing God is not about gathering information – and it cannot be, as there is no information about God to be had.

Even what might look like information about God is actually nothing of the sort. Of course, Thomas wants to say all kinds of things about God, but he insists that these don’t actually tell us what God is like. They might be metaphors (God is a rock, God is a warrior, God is a mother hen), or they might be analogies (God is good, or God is beautiful – though we cannot know what these things mean when they are applied to God). The most accurate things we can say about God are negative things, or Thomas: God is not this, and not that.

But whatever we say about God, Thomas says, even when they are true things, they do not give us information about God as he is in himself. They rather give information about his creatures in so far as they relate to God. This is a bit difficult. Let us put it this way: for Thomas, it is true to say that ‘God is the Creator’, but when we say it we are not expressing accurate information about God. We are expressing accurate information about ourselves: we really are created. It is a fact about us that we are creatures. It is therefore logically true that God created us, but that is not information about what God is like, because being a creator is not what God is like. If it were, then God would have changed from not-being-a-creator before the act of creation to being-a-creator after the act of creation. And of course God cannot change. And also there can be no such thing as ‘before creation’, because time itself is part of creation.

This is why Thomas says that calling God ‘the Creator’ does not actually tell us what God is. It is merely a logically necessary expression implied by the fact that we are creatures.

If God were a being, an individual of some sort, there would be various descriptive things we could say about him more or less accurately, about what he was like. Throughout God as Nothing, however, we deny this possibility. Where the mind quite understandably asks for information, for a description, it cannot find it. What it finds instead is a calling: come and see. An invitation to change your life.

We long to know God, and we do, in Christ. But not through information offered in the indicative mood. We know God by responding to his call in the imperative.

Of course we want to know God. And Jeremiah reminds us that knowing God is not about gathering information at all:

“Did not your father have food and drink?

He did what was right and just,

so all went well with him.

He defended the cause of the poor and needy,

and so all went well.

Is that not what it means to know me?”

declares the Lord. (22:15-16).

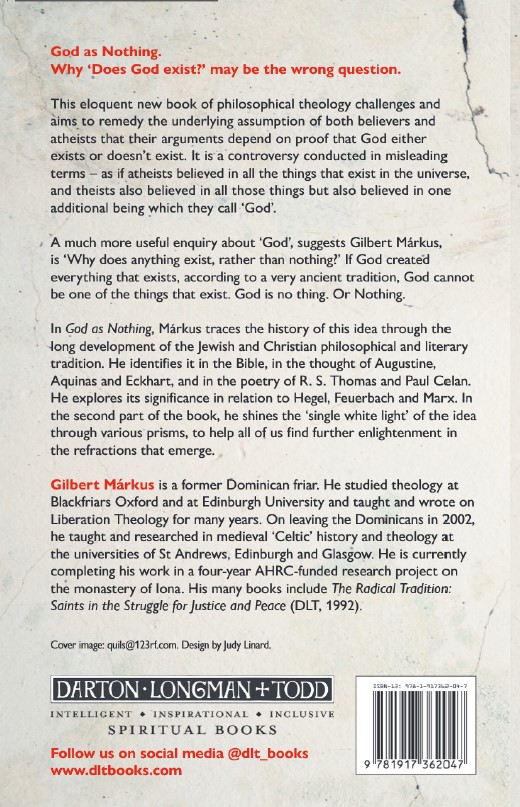

This blog was created to encourage discussion and engagement

with the recently published book God as Nothing, by Gilbert Márkus.

You can order a discounted copy from Writing Scotland here.